A digital pound has been touted as a cheaper, faster, and more modern way of making payments — but not everyone’s in love with the idea.

The U.K. recently doubled down on its pledge to become a “global hub” for crypto — an attempt to entice companies frustrated by a lack of clear regulation elsewhere. Those plans are being pursued with some urgency and could be finalized this summer.

But there’s another area where the country is dragging its heels: whether or not to launch a central bank digital currency (CBDC.) It’s been informally given the nickname “Britcoin” — a clever play on words we’re sure you’ll agree — even though it would be vastly different to the volatile cryptocurrencies dominating the market.

The Bank of England has admitted that a digital pound is “likely to be needed” as Britons go increasingly cashless, but is yet to definitively decide whether to develop one. Consultations have taken place to explore the pros and cons of a CBDC, with economists working on a prototype as we speak.

Setting out the potential benefits, the Bank of England even created a graphic that shows how it could replace coins and banknotes:

Other touted benefits include faster and cheaper payments for consumers and merchants alike — as well as the ability to only release funds when goods and services are delivered.

Given a general election has to be held by January 2025 — and it seems almost certain that the Conservatives will lose — it’s worth looking at what Labour, the party tipped to win, thinks of Britcoin. In a recent document setting out its financial policies, it said:

“Labour fully supports the Bank of England’s work in this area, and wants to ensure that issues such as threats to privacy, financial inclusion and stability are effectively mitigated.”

Labour Party

That sentence neatly touches on several major concerns that critics have about Britcoin.

For one, some MPs and industry experts have raised fears that a digital pound could be used to monitor how consumers spend their money — or even restrict the purchase of everything from flights to red meat. In written evidence to the House of Commons Treasury Committee, the Electronic Money Association trade group warned:

“The prospect of having one’s every transaction observed, stored and analysed in perpetuity is dystopian, and yet within reach. Users’ right to conduct their lives in a modicum of privacy must be maintained in an open civil society, with compromises made only where the financial crime risk warrants such transparency.”

Electronic Money Association

While you could argue that this amounts to fear-mongering and a touch of exaggeration, China has already shown how this can work in practice. Beijing has been streets ahead of developed economies with its rollout of the digital yuan — with People’s Bank of China governor Yi Gang admitting the e-CNY intends to offer controllable anonymity.

Financial inclusion is another concern. More than three million British consumers still rely on cash in their day-to-day lives. Yet, at the same time, ATMs have become harder and harder to find — with some retailers now refusing to accept banknotes altogether. A digital pound may be of little comfort to older Britons who haven’t embraced technology, with research from Age UK indicating that 2.7 million over-65s do not use the internet. While the Bank of England has stressed that a CBDC wouldn’t replace coins and banknotes, and both would continue to be available, this could hasten the switch to a cashless society.

The Treasury Committee’s report went on to warn that the impact on financial stability is unclear — and Britcoin could “increase the risk of bank failures” by making it easier to move funds out of institutions in distress. Limits on CBDC balances have been presented as a potential workaround here.

Overall, there doesn’t seem to be all that much enthusiasm for Britcoin — a clear point of difference that makes it superior to the status quo of contactless payments. Even the Treasury Committee’s report openly wondered whether this CBDC was “still a solution in search of a problem.”

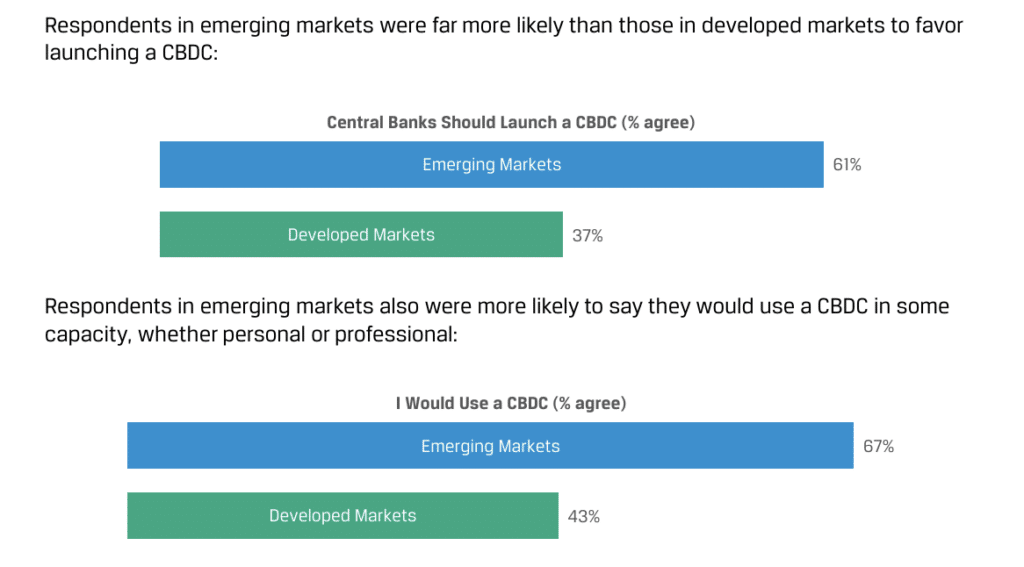

Globally, a recent survey by the CFA Institute indicated that the vast majority of respondents didn’t want their central bank to launch a digital currency — and wouldn’t use it if they did:

Britcoin is unlikely to materialise for years to come — if it ever does at all. Achieving mainstream adoption would involve a huge awareness campaign, eye-watering investment in new infrastructure, and extensive work to assuage the concerns of critics.

And with the U.S. and EU also failing to make cast-iron commitments on whether they’ll roll out digital dollars and euros, we could see privately issued stablecoins fill that void and establish market dominance instead.

This article first appeared at crypto.news